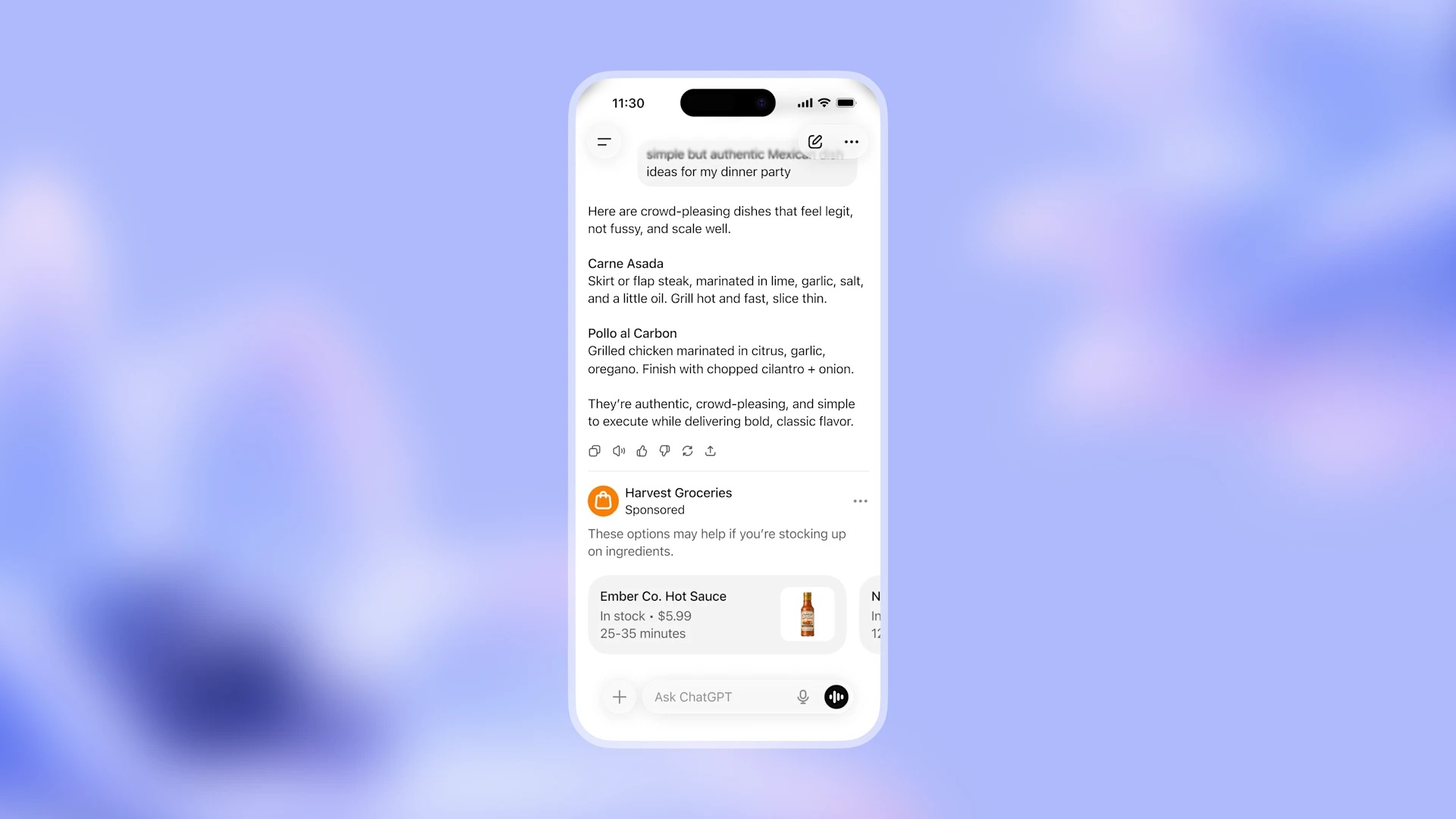

2025 will be a big year. Over the next 11 months you can expect autonomous cars to take your kids to school, women to start wearing one-piece hygienic suits (and move from human to silicon partners), tobacco smoking to vanish, and the very concept of currency, schools, and the internal combustion engine to disappear.

Or… maybe not. As you’ve no doubt realised, these are past predictions about the year 2025 AD, and while the year is still young, none of them seem likely to transpire. Of course, it’s easy to mock the mistakes.

Some, to be fair, were spot on (I particularly enjoyed a letter to The New York Times in 1925, correctly calling that Beefeaters would still be at the Tower of London a hundred years later). But what’s interesting isn’t just that so many forecasts are wrong — it’s that they fail in predictable ways. And that has big implications for how we think about the future of media.

We all need a crystal ball at some point

Predicting the future isn’t just the preserve of futurists and mystics — everyone does it. If your job involves strategy you’re making implicit predictions about the next 12 months (at the very least). If nothing else, consider American inventor Charles Kettering’s words — the future matters because ‘we will have to spend the rest of our lives there.’

I’ve spent a lot of time scouring various archives for predictions made about 2025 in years gone by. For this piece, I’ve plucked out some common ones relevant to the media world, fact-checked them against GWI data, and pulled out the lessons we can learn.

Looking back on the future

Prediction: Virtual and augmented reality will be widespread. Headsets will replace handsets, and smartphone owners will be laughed at.

Reality: Only 5% globally own a virtual reality headset, and just 26% are even excited about VR (16% for AR).

Lesson: We know from our research that the things people care about most when buying a tech device are cost, battery life, and comfort/form factor. Most new devices can’t go mainstream until they meet these criteria, and VR/AR products have largely failed to do so.

Prediction: The print book will be obsolete; all publishing will exist digitally.

Reality: The ebook revolution never quite happened, and looks unlikely to happen in the future. Just 8% own an e-reader, and 51% prefer reading via physical books (vs. 25% for ebooks).

Lesson: We often assume that new technology replaces the old, but the reality is more nuanced. Print books (and vinyl) persist because context matters. Print books are better for reading to children, sharing, and using as decor. Plus, it’s harder to read an ebook in the bath.

Prediction: 40% of the workforce will work outside traditional offices (this 1998 forecast is just one of many on the same theme).

Reality: Surprisingly accurate — 41% now work remotely in a typical week, though this has declined in recent years.

Lesson: The prediction was right, but few foresaw a global pandemic as the catalyst. Nassim Nicholas Taleb warns against assuming the future arrives through incremental change — history doesn’t ‘crawl’, it ‘jumps’. Often the skill isn’t in prediction as such, but recognising black swans when they swim into view. ChatGPT might fall into this category — a transformative force even its creators didn’t anticipate.

Lessons about the future, for the future

Beyond these case studies, here’s some more advice for better foresight, drawn from studying old predictions made for this year.

- Less happens than we think, and it happens more slowly. Change takes time, and it faces friction from cultural resistance, political push back, and entrenched systems.

- Most predictions come from futurists and tech insiders with a vested interest. The best foresight often comes from regular people whose actual behaviour shapes the future more than innovation alone.

- Futuristic forecasts tend to repeat the same tropes. Regardless of when the predictions were made, pundits always seemed to forecast virtual reality, body implants, holograms, and/or ubiquitous touchscreens. The future is messier and harder to imagine than we realise, partly because we focus more on changes in technology than changes in society.

- Old habits die hard. Just look at radio — the medium is now over a century old, surviving all kinds of technological disruption in the process. Even as music streaming and podcasts have grown in the last decade, UK listenership has barely changed.

Whatever our collective consensus of the future is, it’s probably more wrong than right. New tech and behaviours will emerge, but we probably won’t see the biggest ones coming. And when they do, adoption will start fast, but also take longer than expected to reach the mainstream.

And above all — your average Joe probably knows the future better than people paid to predict it.

Featured image: ChatGPT