As podcasting continues to gain popularity in the UK, its influence remains largely unchecked. Should the medium be regulated?

Concerns about the lack of oversight in podcasting came into sharp focus in December, when Steven Bartlett was accused by the BBC of allowing guests to propagate unsubstantiated health claims on his show, Diary of a CEO.

BBC World Service analysed 15 health-related episodes of Bartlett’s podcast and claimed there were an average of 14 claims per episode that contradicted ‘extensive scientific evidence,’ including that autism can be reversed through diet. Just one month before the BBC published the story, Diary of a CEO surpassed one billion streams — a milestone in UK podcasting.

Should the UK media regulator, Ofcom, expand its remit to cover podcasting?

Lots of influence, little responsibility

Podcasts’ appeal lies in their accessibility and intimacy. They integrate into daily routines, with over three in 10 listeners tuning in while cooking (34%), commuting (32%), or walking (32%). This convenience, coupled with the private nature of headphone listening, fosters a parasocial intimacy with hosts — one that translates to trust. Acast reports that 75% of listeners act on product endorsements heard in podcasts.

It’s worth noting that Acast has a vested interest in promoting the effectiveness of podcasts, but there’s no doubt advertisers are catching on to the opportunities presented by the medium. In 2023, UK podcast ad revenue grew by 23% to £83 million, closing in on the £92 million spent on streaming ads, according to IAB UK.

Podcasts also emerged as a potent political tool during the 2024 US elections, as both presidential candidates made appearances on high-profile shows to engage voters.

It’s harder to tell if podcasting has the same influence in UK politics. The relatively predictable outcome of the 2024 General Election meant that podcasts played more of an observational role than a decisive one, compared with US counterparts.

Either way, the lack of guardrails means podcasts can easily become conduits for misinformation. CNN reported that the US president-elect, Donald Trump, made 32 false claims during his three-hour appearance on The Joe Rogan Experience in October.

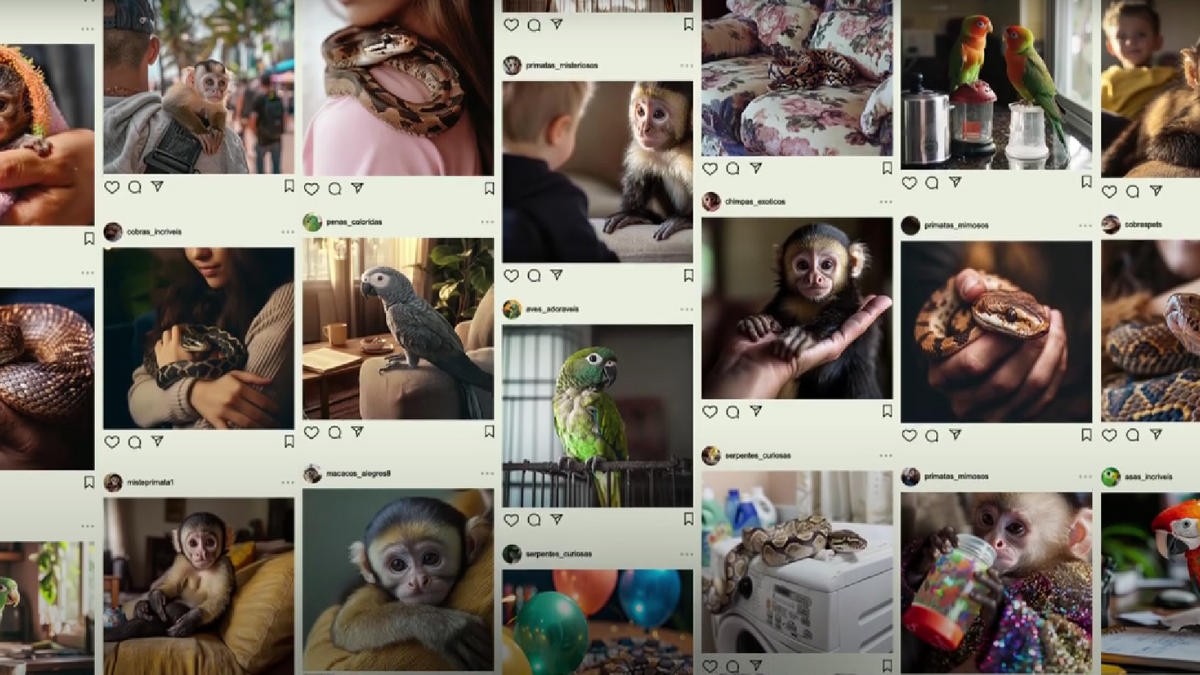

Unlike social media platforms, podcasts operate in a regulatory grey zone. Apple Podcasts and Spotify prohibit hate speech and violence, but offer little transparency in efficacy or, indeed, enforcement. And while podcasts are subject to defamation and copyright laws (in the UK), they are not regulated for accuracy or fairness.

This absence of oversight has made podcasts a haven for fringe voices, amplifying ideologies that might otherwise struggle to find mainstream acceptance. Figures like Andrew Tate have leveraged the format to promote male supremacist narratives, with soundbites generating billions of viral views. The consequences are tangible: in UK schools, children as young as 10 have reportedly echoed Tate’s influence, demonstrating the far-reaching impact of unchecked, extreme ideologies.

But as podcasts are categorised as online-only content, the medium falls outside of the UK’s existing broadcast legislation.

The Media Act 2024, passed in May, marks the UK’s first major reform of media legislation in two decades. These changes aim to address the disparity between global streaming platforms and UK-based services. In February, Ofcom outlined a roadmap to implement key aspects of the Act, which includes a new standards code for Video-on-Demand (VoD) platforms and measures to regulate online TV prominence and voice assistants.

However, podcasts remain notably absent from the Act’s provisions. As highlighted by MP Stephanie Peacock in a parliamentary research briefing, this omission leaves questions about how, or if, podcast regulation might be addressed in the future, despite the growing influence and reach of the medium.

The Canadian model

In April 2023, Canada passed its Online Streaming Act, which empowers the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) to regulate both domestic and foreign podcasts.

Its first policy, issued last October, classified paid, advertising-based and podcasts available on social media as ‘programs,’ bringing platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify under broadcasting regulations.

As Paul Menzies notes, these rules will likely impose a hierarchy of podcasts, as providers adjust their algorithms to promote CRTC-approved shows. He anticipates more visibility for BIPOC, LGBTQ and certified Canadian material, with non-compliant creators sidelined.

The CRTC also clarified that individual podcasters, particularly those whose revenues fall below a specified threshold, and platforms that only act as program guides, will be exempt from these conditions.

Reactions have been mixed. In an article for CBC, policy expert Vass Bednar stresses the need for regulation calibrated to avoid overreach, as the podcasting space is still evolving and requires flexibility. Podcast host Mattea Roach expressed concerns that these rules may disproportionately affect smaller creators, rather than large commercial entities, questioning whether the rules target the right areas.

To regulate, or not

The question of whether Ofcom should regulate podcasts is not simply about curbing misinformation. The medium’s appeal lies in its freedom from traditional broadcast filters — freedom that allows ideas to be discussed but also facilitates the spread of unverified claims.

Calum McCrae, a podcast producer for The Times, pointed out that defining what constitutes a podcast is key: ‘Is it something that goes up on Apple Podcasts, or would YouTube podcasts also fall under the same definition?’

Whilst McCrae acknowledges the need for responsible broadcasting, he added that in an age of growing distrust with the media — highlighted by examples like Meta’s shift on fact-checking—‘I feel it would do more harm right now to relations between government and the public.’

Regulation, if it comes, should be targeted. Instead of focusing on the podcasts themselves, regulators should scrutinise the platforms that control the distribution of content and have the power to amplify harmful narratives through algorithms that prioritise engagement over accuracy. Without addressing this ongoing issue, any regulatory framework risks being insufficient.

As podcast advertising becomes increasingly lucrative, with major players like the BBC entering the market, maintaining a level playing field becomes more urgent. If Ofcom’s role is to protect both content diversity and fair competition, it must ensure that regulatory measures do not undermine the very essence of podcasting while safeguarding against its most dangerous consequences.