I attended the Market Research Society’s annual conference earlier this month and I thought I picked up on a burgeoning appetite for — or at least, an acceptance of — complexity.

It was most stark in the discussion on purposeful marketing. While still broadly supportive of the practice, the panellists were happy to talk about its risks and limits, admitting that the answer to whether or not a brand will benefit from taking a stance on something is usually ‘it depends’.

In the other sessions, too, I noticed speakers were quick to highlight the trade-offs and shortcomings of emerging technologies and best practices. For instance, synthetic data — so often discussed in tones of awe and fear — was downplayed as unreliable, unless it’s tethered to human data.

Not that I’ve ever seen anyone get on stage at an event and say that marketing’s easy — it’s just that I’m used to a bit more certainty. At conferences in recent years, the prevailing sense has always been that, while the road to effective marketing is often arduous, there is a road. Now, that seems less clear.

It may have been that I went to the Market Research Society conference primed to hear about complexity after listening to Karen-Nelson Field and Felipe Thomaz talk about attention for Media Week 2025 the day before.

Clarifying his previously stated objections to How Brands Grow, Thomaz, an Oxford University professor, said the notion that brands succeed by reaching as many people as possible with their ads was based on research that only looked at markets in equilibrium and populated by indistinguishable brands.

Once you step outside of those conditions — and unless you’re marketing defensively from a position of dominance — the argument for simple reach-based planning collapses, he said.

Nelson-Field, an eminent media scientist (and former colleague of Byron Sharp, who wrote How Brands Grow) was just as adamant about the folly of operating ‘reach-based planning in such an unstable media environment.’

Both Nelson-Field and Thomaz are proponents of measuring the quality of attention, but neither think marketers should make it their new obsession. It’s just another metric to add to the list.

Nelson-Field has been preaching the importance of attention for eight years, trying to explain that it’s not a binary, on-or-off thing — if you’re a well-known brand with a strong CTA, passive attention can be great, for example.

But it’s been a slog to get marketers to understand that the level of attention recorded by a device often does not match the experience of the user, and she recalls being shocked at how many of them told her they ‘didn’t want to make things too hard’.

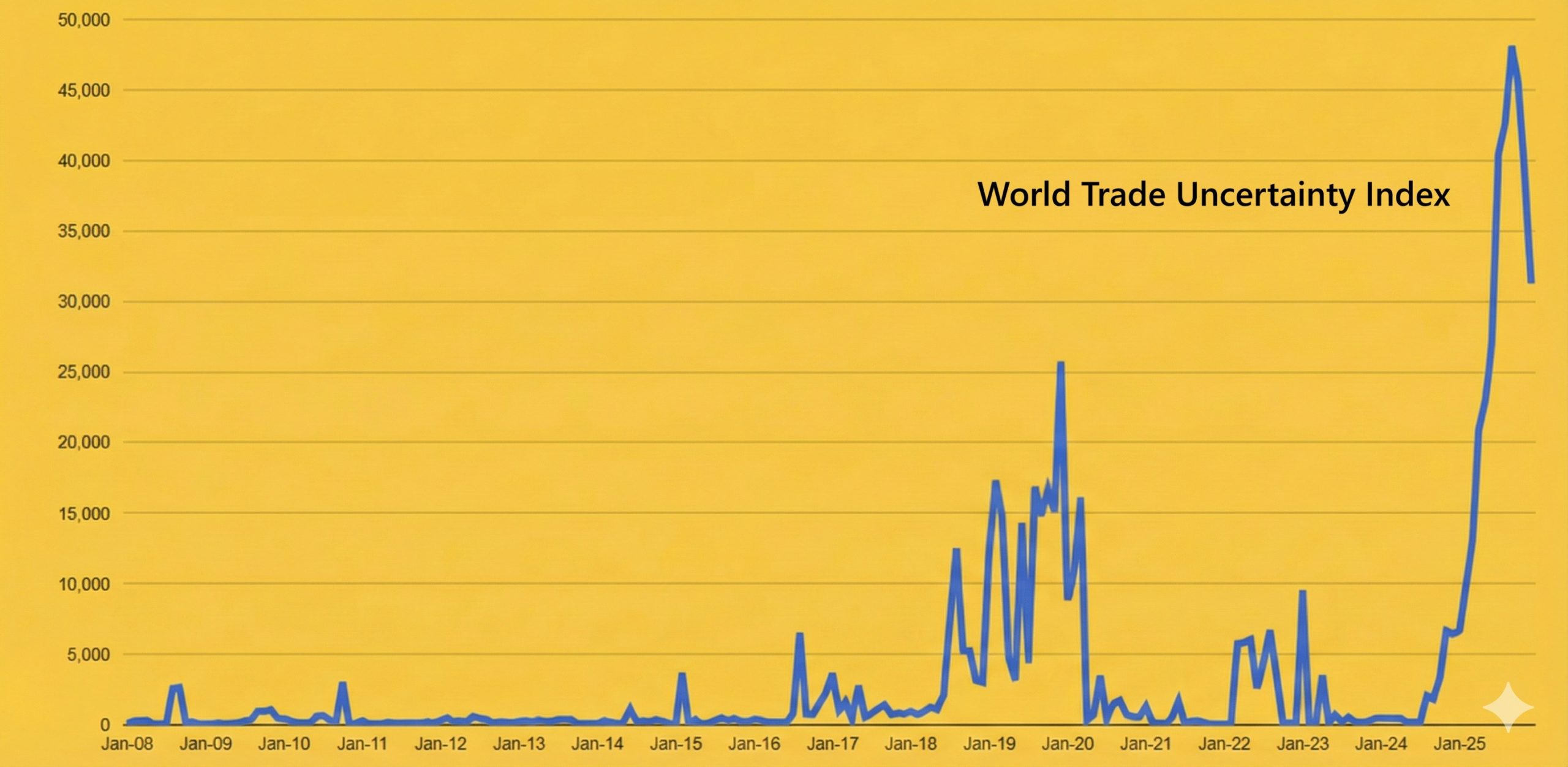

But at least five or six of those past eight years were — in broad-brush economic terms — pretty favourable to marketers. More recently, it’s got tougher. ‘Post-Covid, we’ve noticed that performance marketing effectiveness has been on quite a decline,’ says Ian Gibbs, a data and insight director for the Data & Marketing Association and Jicmail.

Gibbs has spent the past couple of months helping Jicmail promulgate the idea of ‘Super Touchpoints’ — media moments that generate excess attention for brands. Jicmail is always looking for ways to get larger agencies to do direct mail marketing, and the Super Touchpoints framework serves that purpose, too. The hope is that if planners change how they evaluate media, they’ll see the merits of mail. And Gibbs reckons that now agencies are no longer getting the same returns from their existing methods, they’ll be more open to more complex models of effectiveness.

He and I may both be overly optimistic about people’s desire for more complexity, however. Ever since sociologist Zeynep Tufecki wrote about it in 2021, I’ve been following arguments about how screens and social media are nudging societies away from a written culture and back towards an oral one.

Mass literacy is a recent phenomenon in human history, but it changed how populations think and behave by opening the door to complex reasoning and analysis. Before that, in an oral culture, information only survived if it was memorable, by being witty, rhythmic or antagonistic. And for some reason, those are the qualities that tend to get rewarded online and on social media. Even text-based platforms, like X, seem to favour communication styles that have more in common with oral psychodynamics than print ones.

As more of our interactions take place online and on social media, the concern is that we’ll increasingly rely on oral communication styles to be heard, and conceptual, deductive and sequential reasoning will wither.

The more recent arrival of infinite scrolls of curated content online, which encourage passive consumption and context switching, have probably done no favours for our appetite for complexity, either.

Bloomberg journalist Joe Weisenthal has called the return to oral culture the ‘biggest story of our time’. It’s by no means an accepted theory, but there’s enough evidence to make it plausible.

At the end of 2024, Financial Times journalist Sarah O’Connor reported OECD figures that showed an alarming drop in literacy rates around the world (although not in England), with a spokesman for the organisation holding technology partly responsible for the regression.

And earlier this month, data journalist John Burn-Murdoch offered a tapestry of charts and data indicating that people’s ‘ability to reason and solve novel problems appears to have peaked in the early 2010s and has been declining ever since’.

People’s brain capacity isn’t diminishing so much as they are choosing to use it differently. A print culture isn’t inherently superior to an oral one, either. It’s just that a lot of the institutions we’ve come to rely on would probably not survive its absence.

That’s the worst-case scenario, though, and it’s unlikely. Apart from anything else, a defining trait of oral culture — as it was previously understood, anyway — is that it’s ephemeral, and social media has a good memory, especially for things that people would like to be forgotten.

Still, a little vigilance would not go amiss. Not everything has to be complicated, of course — I’m all for simplicity in advertising messages, for example. And it’s also true that complexity can sometimes be used to obfuscate, or to justify inaction. But in the round, I quite like complexity, and I suspect that when it concerns things like systems, adhering to dogmatic simplicity does more harm. In marketing and beyond.

Main image by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash