When OpenAI launched ChatGPT Plus in 2023, the assumption was simple. AI would follow the SaaS playbook: users would pay monthly fees for premium access, enterprises would shell out for APIs — and AI would eventually fund itself.

That assumption is now looking shaky. The arrival of DeepSeek, a Chinese open-source LLM that was built for a fraction of the cost of its rivals, indicates that AI models in the future will be cheaper to run, more available to competitors and, ultimately, more difficult to charge for.

Perhaps this is why OpenAI is now scrambling for a strategic foothold in Asia. If the proliferation of free AI models disrupts the ability of OpenAI and its counterparts to make money from subscriptions, will they turn to advertising instead?

The problem with AI ads

If AI chatbots are supposed to replace search engines, it makes sense to borrow from Google’s ad-funded model. Some companies are already testing out what that might look like. Microsoft’s Compare and Decide ads integrate product recommendations directly into Copilot’s chat responses (which I covered in detail for MediaCat in December).

In November, Perplexity launched sponsored related questions and recently dangled a revenue-sharing programme for publishers — but only when advertisers are involved. Otherwise, their content is still scraped for free.

CEO Aravind Srinivas called the move, ‘a scalable and sustainable way to align incentives for all parties,’ but in practice, publishers have no control over whether their work gets monetised, while Perplexity profits either way.

It’s a clever workaround that highlights a crucial problem: AI isn’t structured for engagement. Google and Meta’s ad models succeed because users scroll, browse and generate repeated ad impressions. AI chatbots deliver direct answers, presenting fewer opportunities to inject ads.

What’s more, the moment an AI response feels biased toward advertisers, users can switch to a free, open-source alternative. Unlike search engines, where brand familiarity and inertia keep users loyal, AI services are fundamentally interchangeable.

Elle Farrell-Kingsley is an AI ethics advisor and policy strategist, recognised for her contributions to national AI governance. Speaking to MediaCat, she warns that ad-funded AI risks amplifying the same opaque profit-driven mechanisms that have eroded trust in existing digital platforms:

‘When revenue models prioritise engagement at all costs rather than ethical AI use, it creates environments ripe for manipulation. The Cambridge Analytica scandal is a prime example of how data-driven targeting can be weaponised to influence behaviour in ways users are largely unaware of.’ While detractors argue that Cambridge Analytica’s impact on voter behaviour was overstated, the controversy remains a cautionary tale of how opaque algorithms can reshape public perception.

Farrell-Kingsley adds, ‘an AI ad-revenue model is clear: maximise engagement, harvest data and monetise attention, at the expense of user data privacy, agency, and societal well-being. There’s a real risk of user data being harvested by third parties, as well as AI making the process of influencing users and creating hyper-personalised profiles on them with more technological prowess and ease than we’ve seen before.’

Is there hope for a hybrid model?

David Pugh-Jones, CMO of AI-powered research engine Corpora.ai, believes AI monetisation will likely mix free, ad-supported access with premium subscription tiers:

‘AI monetisation is evolving rapidly, with ad-supported models mirroring traditional search engines and hybrid approaches resembling streaming platform services. AI-powered platforms that can seamlessly integrate relevant, non-intrusive advertising into their ecosystems will likely drive this shift, creating a balance between user experience and monetisation.’

But will users continue to pay for AI? Wensupu Yang, futurist and founder at KWiM, notes that infrastructure demands make self-hosting impractical for most businesses, keeping AI services commercially viable:

‘Even with continuous advancements in open-source AI models, I believe that for most consumers and non-tech businesses, the technical expertise and computational hardware required for self-hosting will remain significant barriers. Therefore, AI service providers still have a valuable role and can justify charging for their services.’

At the same time, open-source AI doesn’t necessarily mean democratisation. As Yang reminds us, Big Tech still controls who profits: ‘One practical reason for-profit companies choose to open-source their products is to gain wider adoption and establish themselves as industry standards.’

So if ads aren’t sustainable, and open-source AI still needs major infrastructure — where does the money in AI lie?

The real winners are in the clouds

The AI industry’s biggest winner isn’t OpenAI, Anthropic, or any other startup promising ‘disruptive’ models. It’s whoever owns the infrastructure AI runs on.

As Ben Thompson at Stratechery points out, ‘A world where Microsoft gets to provide inference [using AI to make predictions] to its customers for a fraction of the cost means that Microsoft has to spend less on data centres and GPUs, or, just as likely, sees dramatically higher usage given that inference is so much cheaper.’

If AI inference is becoming cheaper, companies that own cloud infrastructure can profit simply by running AI models more efficiently than competitors — reducing reliance on ad revenue.

Microsoft and Amazon are well positioned here, and Apple has an even simpler solution: make AI run on-device. DeepSeek’s efficiency improvements align with Apple’s existing low-power, high-efficiency silicon strategy, meaning AI could become a seamless feature of future hardware, rather than a separate subscription service.

If the real winners in AI are profiting from cloud hosting or device integration, does that leave ad-funded AI as an option only for those without infrastructure dominance?

Who loses?

If AI goes ad-funded, Google is in the most precarious position. Search is Google’s primary revenue engine, and AI threatens to cannibalise it.

If users stop clicking on search links because AI delivers direct answers, then Google’s advertising model starts to erode. This is a much bigger risk than Bing AI ads or Meta’s AI-enhanced targeting, as it challenges the core mechanics of Google’s business.

Thompson notes: ‘A world of decreased hardware requirements lessens the relative advantage they have from TPUs. More importantly […] zero-cost inference increases the viability and likelihood of products that displace search; granted, Google gets lower costs as well, but any change from the status quo is probably a net negative.’

Even Google’s AI chatbot Gemini is a risk factor; it may become a successful AI assistant, but if it diverts users away from traditional search, Google is effectively competing against its own ad model.

AI-first startups are also in trouble. The VC-backed thesis behind AI assumes that AI models themselves will be a product worth paying for. But if open-source models continue to improve, and Big Tech controls the infrastructure, AI startups that don’t own distribution or hosting will struggle to remain profitable. If direct sales start to stagnate, will advertising become the fallback monetisation model?

Tech futurist Adah Parris sees this as part of a broader, extractive shift: ‘AI is already being shaped by advertising incentives, and now we’re just focusing on how we can use it to shape and cajole individuals. The AI itself is not bad. But if we poison the water upstream, we cannot stand downstream with a filter and expect to remove all the crap.’

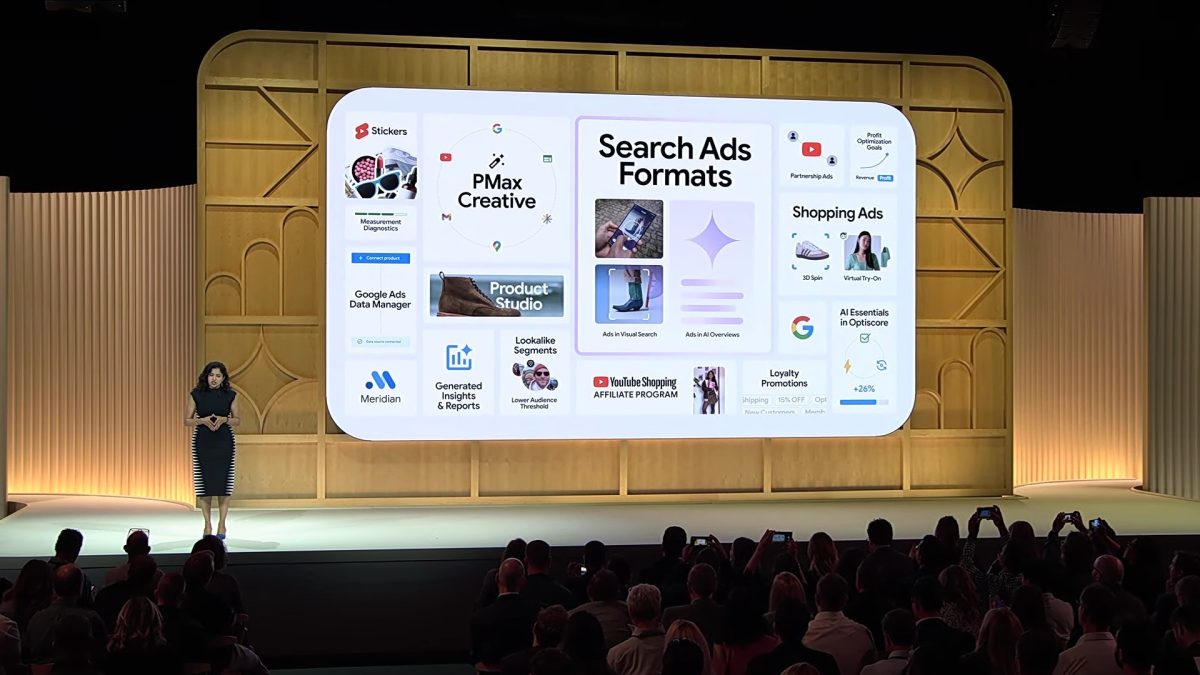

Main image: Google VP Vidhya Srinivasan at the company’s 2024 Marketing Live showcase.