‘Every four years or so a new customer acquisition model disrupts the advertising landscape,’ Bank of America analyst Omar Dessouky told The Wall Street Journal earlier this month.

TikTok was the last one to do it, said Dessouky; AppLovin is being tipped as the next.

The company is king of ad tech mountain after its ad revenue rose 75% to $3.2bn in 2024, decisively out-earning the incumbent market leader, The Trade Desk, which made $2.4bn.

AppLovin made its fortune by figuring out how to place ads for mobile gaming apps within other mobile gaming apps in a way that was profitable for everyone involved. But it’s the company’s expansion into ecommerce advertising that’s triggered all the hype.

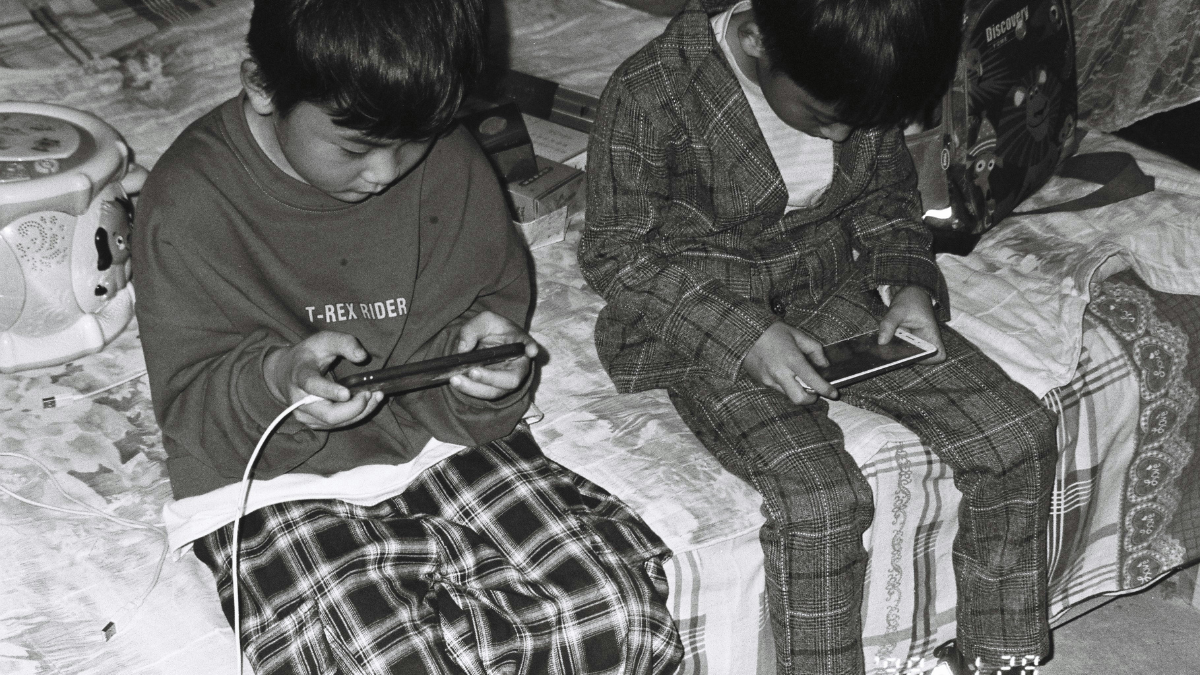

Mobile gaming is kind of a murky industry. It’s not quite cigarettes, but it’s not roller coaster manufacturing, either. Mobile games are generally free to download and make their money by selling in-game items — a shiny outfit for a player’s character, a herd of llamas for their virtual farm, etc — to a tiny minority of users, and by showing ads to the rest of them.

Historically, the vast majority of ads within mobile games promoted other games. Developers don’t really want to show their users ads for competitors, but the inventory is sold at auction and rival developers usually bid highest, so they don’t have much choice. But what developers can do, says analyst Eric Seufert, is make sure that the 3% of users who actually spend money on in-game features never see those ads within their apps.

Why then, would rival developers pay to reach a bunch of freeloaders? Well, because ad platforms like AppLovin shoulder a lot of the risk. Developers don’t pay AppLovin for reach, they pay for conversions — for people to install their game, or to play it for a certain length of time. And developers are happy to pay to acquire users, so long as their data shows (or they’re just optimistic) that the price is lower than the average lifetime value they can extract from those users.

So, AppLovin’s business is essentially an arbitrage. (It does also own a bunch of mobile games, but it’s selling those, so ignore that.) The company has spent the past few years gobbling up data from the demand and supply sides of the mobile gaming market to feed its models, so it can predict whether it can deliver those conversions for advertisers profitably.

The data isn’t perfect, but it’s about as good as it gets since Apple introduced its App Tracking Transparency protocol. AppLovin can work out with good-enough precision which ads perform well in which games, and what a conversion is worth to an advertiser, to come up with a price that satisfies both the advertiser and publisher apps while leaving enough to take a healthy cut for itself.

Before it became Wall Street’s darling tech stock, AppLovin had a relatively low profile because direct response advertising for mobile games isn’t very sexy. But its network of mobile gaming apps reach more than a billion daily active users, which is in the same ballpark as Meta and TikTok. It’s reportedly a valuable audience, too, because it skews towards older women. And now that audience is starting to attract ecommerce brands.

These ecommerce advertisers buy the same full-screen video ads (with a button that takes you to their app or website) from AppLovin as mobile game developers. There’s just a lot more of them.

‘There are over 10 million businesses worldwide who advertise online that could eventually use our platform profitably,’ said Adam Foroughi, AppLovin’s CEO, during the company’s most recent earnings call. And thanks to its acquisition of Wurl in 2022, AppLovin will likely branch out from apps to sell ad space within Connected TV channels in the near future, too. But what Foroughi seemed especially keen to stress was that right now his platform offers advertisers access to an untapped market.

‘[Consumers are] discovering new products while playing the games they love, generating truly incremental demand,’ he said. ‘By enabling these discoveries, we’re expanding the global economy for consumers and advertisers alike.’

In December Haus, a company that helps marketers measure ROI, ran some tests on the platform for ecommerce brands, who spent between $10,000–$60,000 per week, and it found that, although efficiency of the media ‘varied considerably between brands’, in all four cases, AppLovin ‘drove incremental lift’.

AppLovin also makes it easy for advertisers by telling them to just use their best Meta video ads rather than create something bespoke. And its default attribution metric is seven-day clicks, which shows confidence. It also means that advertisers see a return on their investment almost immediately. So, when it works, AppLovin is basically a way to buy revenue.

What AppLovin seems to lack, though, is evidence that it can work for brands on a large scale and bring in customers beyond the low-hanging fruit.

The sceptics’ view is that AppLovin is successful because high quality, full-screen, not immediately skippable ads are still a bit of a novelty in apps, and once this wears off, returns will diminish. It could also be that AppLovin’s price advantage gets chipped away if Meta and other platforms catch up to its racket. And it’s probably not great that, according to Ilkka Paananen, the CEO of mobile game developer Supercell, in 2024 most people were playing games created more than six years ago.

Those niggles aside, it’s good that brands have another customer acquisition channel beyond the established internet behemoths, and you have to give AppLovin credit for how it’s gone about turning an unloved medium into a lucrative business.

Foroughi’s claim that mobile gaming users are a pie-expanding market unto themselves seems a bit grandiose, though, and amid all the talk of revolution and disruption, it’s useful to keep a bit of perspective.

‘I can see why they’re growing,’ Hannah King, founder of media agency Adfabric, told me. ‘The easy plug-and-play-type solutions that are immediately trackable appeal to short-term focused, less savvy marketers who see AI and think it’ll take the hassle out of proper planning work.’

But, she added, ‘You can’t compare to TikTok — which has been a cultural phenomenon, blurring the lines between content and advertising for a lot of brands — something that delivers potentially smartly targeted lipstick ads to someone playing candy crush.’