Financial Times journalist Elaine Moore began the year by lamenting that today’s A-listers aren’t famous enough to draw big crowds like the screen icons of the past.

Young stars, like Zendaya and Paul Mescal (both 28), are struggling to open movies on the strength of their name alone because they can’t cultivate cross-generational audiences, notes Moore. Even Mr Beast, who has hundreds of millions of YouTube subscribers, ‘could probably trip over the average 45-year-old without being recognised’, she says.

But rather than accuse the new generation of celebrities of lacking talent or charisma, Moore blames the proliferation of content and recommendation algorithms. Giving people more choice over what they watch and nudging them towards things they already like, she says, has ‘atomised’ fame.

I usually have no truck with claims that fundamental sociologies like fame are changing. Most of the time, technology just gives people new means to satisfy old needs. But evidence that fracturing media consumption makes superstardom all but impossible is stacking up.

The theory is backed by a plausible rationale, too. If mega-fame requires social proof then it’s not enough for someone to have mass appeal; the masses have to see the evidence of that appeal in each other, too. And opportunities to demonstrate that kind of influence are few and far between in a fragmented landscape.

Taylor Swift (no relation) is the only celebrity I can think of that has gone stratospheric in the past few years, and I don’t think she could have done it without performing in front of tens of thousands of people at every stop of her mammoth world tour.

The same dynamics neutering movie stars are also forcing marketers to rewrite their playbooks, says Tom Roach, Jellyfish’s VP of brand strategy, who’s beseeching the industry to accept that brands should be built with hundreds of smaller activations and partnerships, not just a few gorgeous and clever commercials delivered to a captive nation.

Dr Grace Kite, the founder of econometrics agency Magic Numbers, sees the future of advertising as ‘lots of littles’, too. Synergies between media channels used to account for around 20% of a campaign’s effectiveness, she says. Now it’s more like 40%.

As to whether brands can still achieve pre-fragmentation levels of fame, Kite believes it’s a ‘live question’ that needs more research. But she’s optimistic. Either way, brands are going to have to be more organised to achieve any kind of success within the new ecosystem.

Campaigns must be orchestrated so that ads appear in the right places and at the right times, and so that the executions all gel in the minds of consumers to form a cohesive message. ‘That’s the thing with lots of littles,’ says Kite, ‘it all has to match up.’

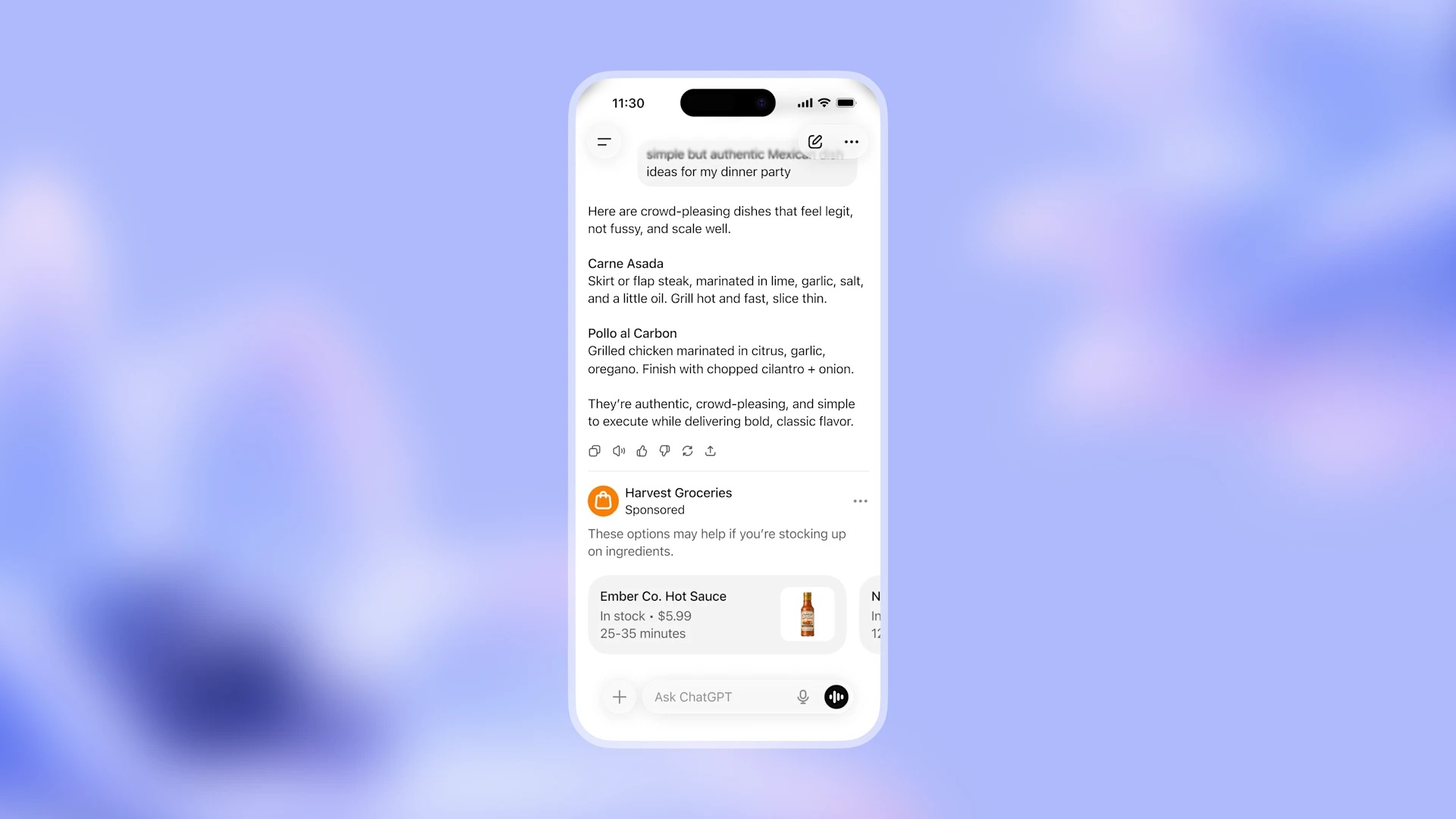

AI and tech will do the heavy lifting of planning and executing these ‘lots of littles’ media strategies because it’s too complex and unwieldy for people, not least because campaigns must now satisfy the caprices of the algorithms, as well as engage potential customers.

I get why marketers are reluctant to think about advertising as lots of littles. The history of the industry is the history of mass media, and linear TV still delivers as a mechanism for brand building. But the viewing figures show that it is unlikely to be the case much longer, warns Kite, and while online video shares some qualities with TV, it doesn’t have the same effect on people’s attention. If another medium is going to arrive that can do the same job that TV used to do, it’s going to have to hurry up about it.

Back to Hollywood. In an interview published last year, a GQ journalist asked George Clooney and Brad Pitt why so few movies were now marketed to audiences on the strength of actors’ names alone.

Clooney explained that it’s because studios no longer groom actors for stardom with carefully planned multi-movie deals. Still, he says, it’s better to be a young actor today: ‘When I was a young actor, if you looked at the back of the LA Times every Monday morning they had the 64 shows that were made […] But that was it. And then the studios were doing five films a year. Now […] there’s a lot more work.’

Kite thinks the ad industry should adopt a similar perspective: ‘We can’t moan about what we have lost. We have to see the benefits of what we’ve got now.’

Main image Photo by Marius GIRE on Unsplash