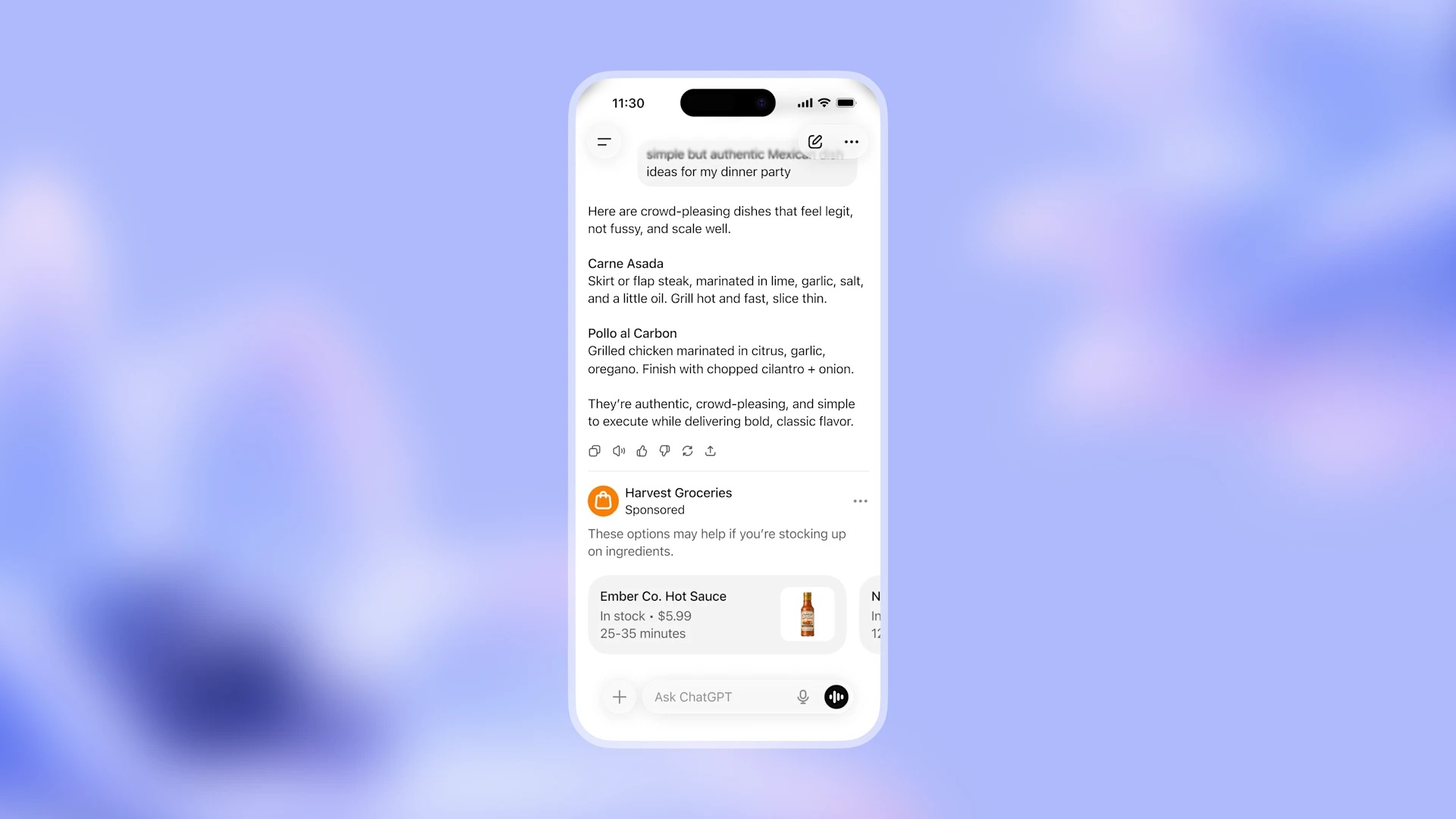

When Wavemaker’s strategy partner, Faye Longega, started mapping trust in brands against perceptions of their quality, she didn’t immediately find a correlation.

Speaking at a Thinkbox event on 5 November, Longega explained that patterns only emerged when she grouped the brands into product categories.

‘Eighty-eight percent of the 145 categories showed moderate-to-strong correlation between “best brand” and “trust”,’ she said.

The reason the data only makes sense when brands are grouped by category is that people’s expectations seem to vary greatly depending on what they’re buying: lumping all the categories together leaves you with a jumbled mess.*

Longega added that the highest correlation between ‘trust’ and ‘best brand’ was in so-called high-risk categories, which includes condoms and weight loss drugs, movies and opticians.

In high-risk categories, trust in a brand goes hand-in-hand with perceptions of quality, and gaining people’s trust is likely most valuable in terms of gaining purchases.

‘Functional’ and ‘low risk’ categories — like cafés, chocolates and soaps — showed a much weaker correlation.

Longega suggested that these are brands where some degree of trust is needed to consider a brand good or the best, but that other considerations might play a larger role in a purchase decisions.

I agree, and would also suggest that these are brands where the perception of brand values, and an awareness of how other people view the brand, are just as likely to influence a purchase as trust.

This theory would tally with the handful of categories that showed no connection at all between trust and best brand perception — namely, sports teams, fizzy drinks and AI.

Longega pointed out that these are categories where a customer may not see a huge amount of value in trust.

‘Do you really need to trust a sports team?’ she asked. ‘Maybe you do, but it’s more about the emotional connection. Fizzy drinks is a bit more about taste, preference, but do you really need to trust fizzy drinks?’

Longega said that she ‘doesn’t really know’ why AI is grouped with this kind of product. She guesses that, as a very new product, it might behave a little differently. I would suggest that, like the low-correlation categories, however, these are all areas where outside perception might have a stronger role to play than brand trust.

For example, I might be 100% sure that AI will be the death of culture or that Fentiman’s Curiosity Cola is a superior product, or it’s possible that I more motivated by the fact that I really want people to see me as the kind of person who’s sceptical about AI and drinks that beverage. I think to a lesser extent, the same is true of my purchases in the low-risk and functional category which showed low associations. I do want to be seen as someone with good taste in soaps and chocolates, maybe more than I want my soaps and chocolates to be trustworthy.

There are even some categories where an inverse correlation appeared in Longega’s data, all of which was taken from WPP’s Brand Asset Valuator tool.

‘This is where, the less trusted you are, the more likely you are to be seen as the best brand,’ she explained. These categories were perfumes, political parties, and jams.

‘Perfumes are probably about distinctiveness and uniqueness, so maybe being trusted is seen as being bland and boring,’ she suggested.

I know that my preference for Sabrina Carpenter’s Sweet Tooth perfume line is more to do with the fact that the bottle goes with my bathroom decor than whether I think it’s the best scent. It’s certainly not a rational choice of which perfume I trust most.

Longega was more sure-footed on why crafty political parties might be viewed as more competent, suggesting that most people believe success in politics — ie, getting and staying in power — requires Machiavellian tactics.

Jams, though, remain a mystery. ‘I have absolutely no idea,’ said Longega, ‘If anyone can try to explain that to me at any point, please do.’

Are people as clannish about Bonne Maman vs Hartley’s as they are about Coke vs Pepsi? Are consumers on the hunt for a unique, game-changing jam or a jam that will lie to you but get the job done?

More data needed.

Image by Deon Black on Unsplash

*If you really want to know the details: The reason that the data only makes sense when brands are grouped by category is that the variance between the lowest point (the least trusted brand and the one least likely to be perceived as the ‘best’) and the highest (the one most trusted and most likely to be perceived as best) differs for every category. This makes the across-category data look disconnected, even though most categories follow this pattern.