In September, the IPA published the seventh edition of its Making Sense report, which documents how media consumption habits are changing in the UK.

Simon Frazier, the institute’s head of marketing and data innovation, wrote the latest report. He also wrote the previous six editions, so we thought he’d be a good person to ask about how media consumption in the UK is evolving, and what these shifts mean for media planning and buying.

Below is an edited account of our interview.

The IPA’s annual Making Sense report charts how UK media consumption evolves. What are the most significant shifts that you noticed in the recent seventh edition?

What’s quite striking is that we talk about the complexity of the media landscape, how everything’s shifting, and how it’s harder to reach people and build scale, and I think what happens is you end up analysing everything separately and don’t really see the joined-up picture.

One of the things that we do with the report is group together all media consumption into video, audio, text and out-of-home. And what I’ve done over the years is create a line chart which plots the reach of those. Every single chart — excluding the ones that happened within the pandemic — is identical.

So despite the fact that video went from being majority TV or cinema in 2005, to broadcast video on demand, subscription video on demand, linear, social video, etc, the patterns of consumption haven’t changed at all.

So the need states that media are addressing are very constant, and I think once you get away from the idea that none of the old rules apply anymore, [you realise people’s] daily lives haven’t been seismically impacted by these shifts in media consumption because they’re still doing the same types of things at the same times.

There’s more fragmentation but, most of the time, if video attention is not going to one type of video, it’ll be going to another.

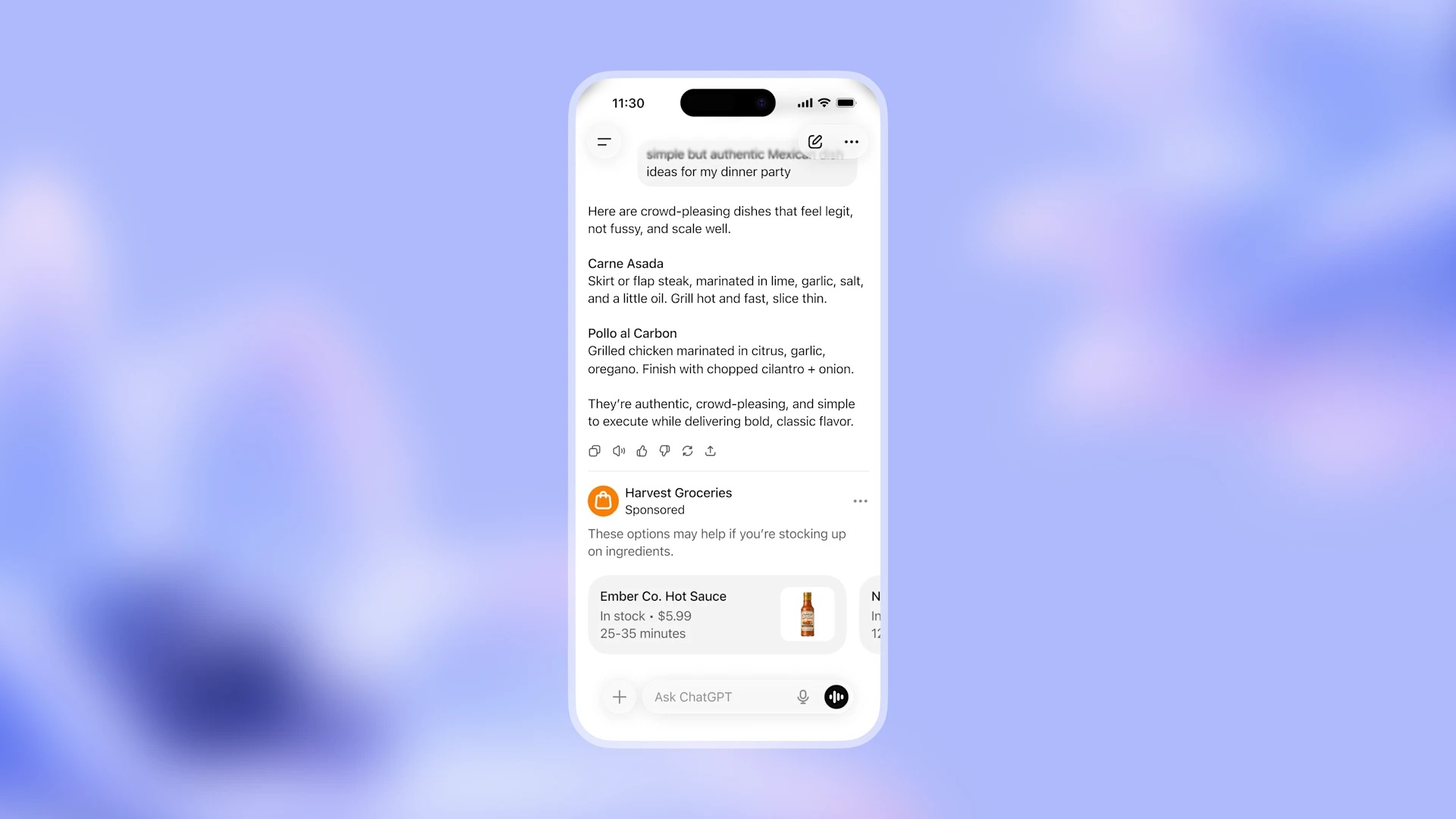

Another thing I think is quite striking and quite positive is, as we’ve had increased fragmentation of the streaming landscape, the increase in choice is resulting in a more interesting advertising landscape because limited consumer budgets mean [streaming platforms] are having to adapt their revenue models.

The trade-off [for consumers] between saving money and accepting ads seems to be a fairly easy one to make, so what we’re seeing is the share of time spent with commercial media is increasing. Back in 2015, about 66% of media time was spent with ad-funded media. Most of the rest was spent with BBC content. Then we saw the growth of streaming services, like Spotify premium, eroding [ad-funded media’s] share. That was something the industry was really worried about because people were saying it was impossible to reach 16-to-34s behind these paywalls.

Now the share taken by commercial media is at 67%. You may say it’s only 1% higher [than it was in 2015], but it’s actually a lot higher than it was within the interim years when that share had really dropped down.

I think 70% of 16-to-34s media time is ad-funded now. So, the opportunities to reach audiences at scale are absolutely still there, but you just need to use more varied media offerings, and that makes it more fun.

Does advertising lose some of its potency when it’s being delivered to audiences that are fragmented across lots of different channels, though, rather than within an environment where everyone is watching the same thing at the same time?

TV can absolutely still deliver phenomenal scale for brands. And the buzz around TV moments on social can actually make things feel a lot bigger than they are, in some regards. Succession is a good example of that because the early-series viewing numbers were pretty low but the buzz around it was massive, and then as time went on, it built up. So it was one of those things where people were late to the party, but when the party got started it was bigger than it would have been before.

Do you think that by encouraging SMEs to broadcast advertising, that TV will lose some of its costly signalling effects?

I was thinking about this recently. The thing I like about US TV is, if you’re in Missouri or somewhere like that, you’ll see an ad on the TV on what seems like a fairly mainstream channel for a bed shop that’s down the road. And you’ll have the owner, who thinks he’s the real onscreen talent, doing a fantastic job selling you the product in a way that’s actually quite counter to traditional advertising models.

Does it diminish [the costly signalling effect of TV]? I don’t think it does. I think the localisation or the personalisation of TV is really valuable, in terms of embedding a sense of local community.

And as TV becomes increasingly addressable, that makes it more interesting. But it depends on the quality of the ads, to be honest. I know that there have been a couple of TV channels that have started AI studios to enable [brands] to create short ads, and from what I understand, the uptake of that hasn’t been as expected. I don’t know if that’s a creative issue or whether, for brands that are used to performance metrics, TV might be too much of a risk.

What do the consumption shifts that you’ve observed mean for media planning, then?

The fragmentation of the media landscape reduces the requirement of putting all of your budget into one specific channel, which could go catastrophically wrong, if it’s not done properly. So media planning is more exciting than it’s ever been because there are a lot more tools to play with.

There’s always a lot of chat around AI and its abilities to do media plans, but the angle I would take against the idea that AI can replace media planners is that every single medium requires a very different approach. Not only that, the information in the public space that has been used to train AI systems is poor on media planning.

That’s why it’s so important to have the expertise of great media planners, which is not always rational or logical, and may be things that they just know intrinsically from years of experience that an AI system might overlook.

Another problem is that if everybody’s using AI then what’s the point of differentiation between agencies? It comes back to how they think differently and how they apply it.

Working at the IPA is an enormous privilege in that I get to kind of go behind the scenes at so many different agencies, and they’re all taking very different approaches.

What kind of approaches have you seen?

One of the approaches that I saw was [the agency] used AI to analyse the campaigns of brands within the same category and the thing that came out was they weren’t using traditional media. As a result of that they then tried a targeted direct mail, and I guess the strangeness of that for the category made it immediately memorable and also generated shareability on social.

What do you make of this idea of systems planning? Is it something genuinely new and useful?

It’s new skin for old ceremony. Fifteen years ago, Vicky Fox [chief planning officer at Omnicom] was thinking about ecosystems with cross-media planning.

So, cross-media planning, systems planning and full-scale campaign reporting using quality de-duplicated data to understand reach and frequency across multiple channels has been really important for a while.

The systems-led planning approach enables you to understand brand fatigue, it enables you to understand context and to vary messaging by moment and optimise according to the environment that you’re in. And data certainly does enhance that [ability], but the challenge of saying everything should be [focused on] outcomes is that you can get trapped in situations where you’re over investing or over optimising in one channel without seeing the impact it’s going to have on the wider media plan.

Having said that, there’s some other really great approaches being done [by agencies]. Hearts & Science have done some absolutely fascinating work on category entry point planning, pulling away from understanding the audience to really understanding the need state.

They’ve done some amazing work for Win Win, which is a national lottery, understanding how they can vary the lottery’s offering, and understanding the context of why people make a particular decision around each of those.

I’ve also seen marketing commentators talk about this as advertising’s outcomes era. Is there anything substantive behind that idea?

I think the idea of an outcomes era of marketing is largely driven by the increasing speed of information, and also, as the landscape’s fragmented, there’s more requirement for the justification of why we would use this media channel or this media property from a client side. I absolutely understand that because you want to take a calculated risk, you don’t want to take a punt or a gamble.

But we’ve always been planning for outcomes. When people invest in TV, yes, they use the proxy of reach and frequency metrics, but they also know there’s huge amounts of studies into what kind of creative is going to work well in particular environments.

Having said that, one of the challenges of trying to apply outcomes-led approaches to all media is they don’t all work in that way. Cinema, for example. If you’re looking for specific outcomes, even if it’s brand uplift, it’s harder to justify that using an outcomes-led approach.

And that makes it harder to build brands in meaningful ways. It may be easier to build brand awareness, it may be easier to build brand recognition, it may be easier to drive short-term sales, but it’s harder to build warm perceptions of brands amongst consumers because consumer perception is built over years. And the more we’re moving towards the required measurement of absolutely everything, the harder it is for planners to use anecdotal common sense. It becomes harder to go, ‘That doesn’t feel right to me’.

Main image created using Google Gemini