Do you know what song was the UK Christmas number one? No one (in the UK) that I asked while writing this did. When I was young, in the beforetimes of mass media, Top of the Pops was a cultural barometer. It was the world’s longest running weekly music show, until it got cancelled because it had come to its ‘natural conclusion’, according to the BBC’s director of television. The charts tell us what other people like, a form of social proof, leading others to discover it.

Last Christmas the number one song in the UK was Last Christmas by Wham, as it was the year before. This is unusual.

For the five years before that the Christmas top spot was held by the same artist (whom I have never heard of) called LadBaby, with a series of sausage roll themed novelty songs, launched from YouTube. That is also historically unprecedented, surpassing even The Beatles’ run of four Christmas number ones. However, as I said at the top, no one seems to really even notice anymore, although there is age bias in my unofficial sampling, since I only asked adults. As I’ve pointed out many times before, things can now be ‘famous’, and yet invisible to most.

Regardless, there is something strange happening to media products. Media goods are economically known as non-rivalrous, because consuming a song or TV show doesn’t mean there is less of it, as if it were a regular (rivalrous) commodity like grain. In fact, media has the opposite quality, which is to say it becomes more valuable the more it is consumed. The more people buy or stream a song, or watch a television show, or read an article like this one, the more value it accrues, either directly through purchases, indirectly through influence, or by aggregating and selling the audience to advertisers.

When something gets slightly more awareness it becomes subject to cumulative advantage, because desire and preference for aesthetic goods is highly memetic. This was demonstrated in various closed-world experiments, using music by social scientist Duncan Watts. Essentially, if no one knows any of the songs, they become popular randomly within the closed groups. There is no objective way art of any kind can be good or bad.

If it is famous, it is valuable, and if it’s not, it’s not. Hence the business of art, and of media, is fame.

In the real world when a media product becomes well known enough, it is subject to network effects because people either talk about, share, or use it in some way, perhaps as shorthand, perhaps to inculcate some community of interest around it — fandom — or to experience something together — parties, concerts etc. This is why media goods tend towards power-law (long tail) distributions — a few things are famous and get more famous; most stuff few people see. Few artists can fill stadiums anymore. Hence the portfolio model of record labels and movie studios and publishers — because the dynamics of popularity are, to some significant degree, random, they have to hedge bets across a number of products to get decent returns within the risk profile of the business.

The very nature of media as a business relies on these effects and monetises accordingly. People develop parasocial relationships with TV presenters or pop stars, and stan (a term for a fan, originally short for fanatic, derived from an eponymous Eminem song about a fanatical fan) them, supporting and propagating their work on social media, for example, which further amplifies their value. They may even buy your memecoin or digital trading card.

Now we have AI. Noah Brier, co-founder of AI consultancy Alephic, refers to AI as a ‘fuzzy interface’ because it ‘can act as the bridge at any point in the process where you need to transform data in one format into data in another.’ This suggests we are approaching the possibility of what Negroponte called ‘bitcasting’ in Being Digital (1995): ‘Bits are bits. The six o’clock news not only can be delivered when you want it, but it also can be edited for you and randomly accessed by you. If you want an old Humphrey Bogart movie at 8:17 pm, the telephone company can provide it over its twisted pair. Eventually when you watch a baseball game, you will be able to do so from any seat in the stadium or, for that matter, from the perspective of the baseball. These are the kinds of changes that come from being digital, as opposed to watching Seinfeld at twice today’s resolution.’

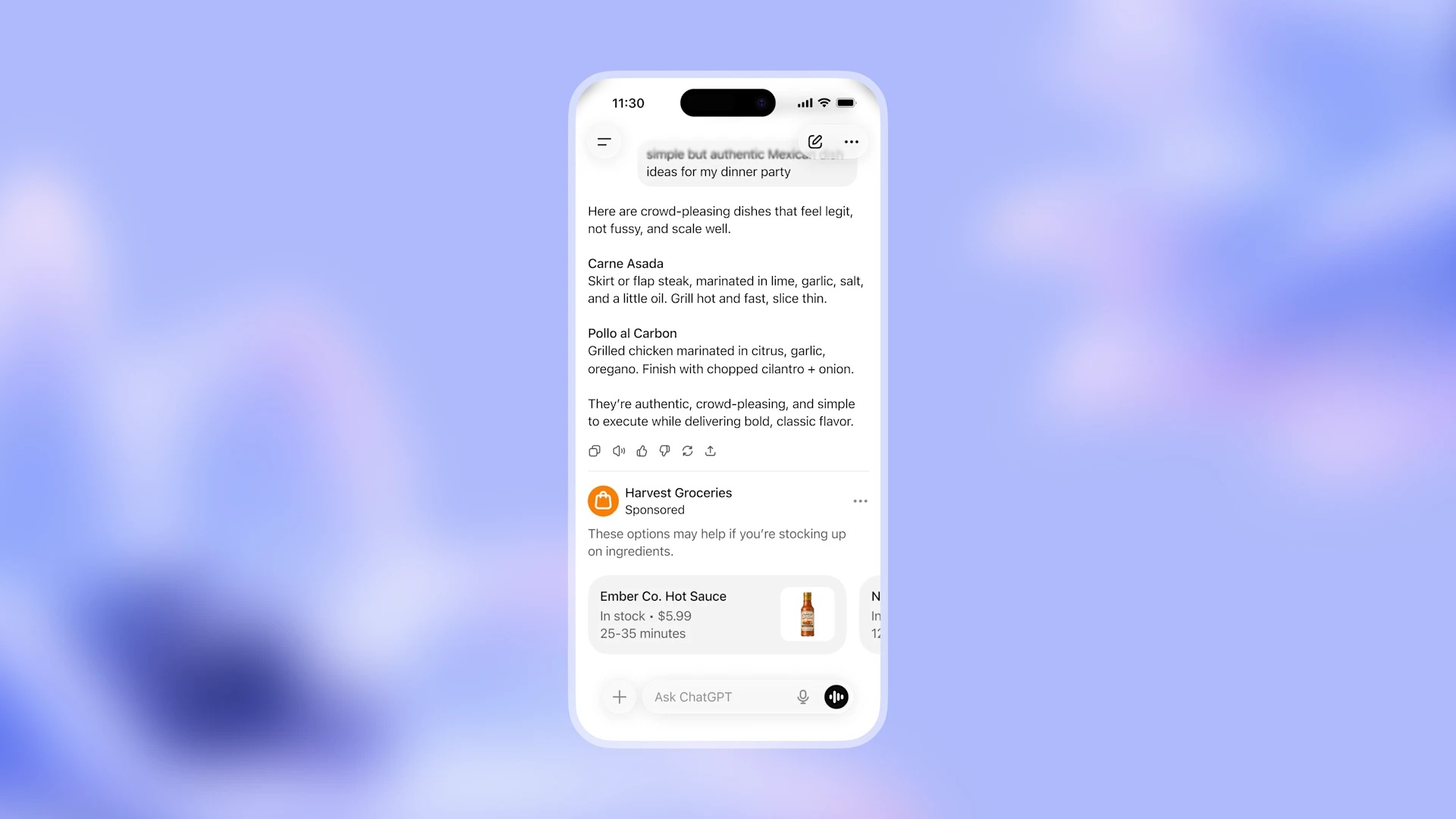

So we can imagine the news, or any other bits, being tailored to our interests and rendered in any form we choose — audio, video (of any kind, with any person), text (in any language or style) or some virtual experience (lol). The more personal our media becomes the less it can operate via network effects, to create cultural cohesion or connection. Culture splinters into individual shards: but how does media work, commercially and socially, when only you see what you see?

If you want Bogart to play Beetlejuice with a Sondheim score, you will be able to have it rendered instantly — but that kind of personalised content relies on existing references, things that already are famous, prior art. Songs that only you ever hear, created by/with AI, might fulfil all your aural desires, but no one else will have heard them.

For example, here’s one I made earlier (Blue Peter IYKYK) on Suno about this article: No Top No Pops

It’s a banger, within my frame of preference; but is unlikely to become famous (and even if it did I doubt I own the copyright. The US courts have ruled that anything AI generates without human input can’t be copyrighted. Does my prompt count as input? What constitutes ‘authorship’ when working with AI?).

How does audience aggregation around content work with personal media?

Why was Last Christmas number one last Christmas and the one before?

Humans evolved as social creatures, hence the use of symbolic language, which is unique to us. We evolved communication to allow us to act in groups to hunt bigger animals, with all the attending complexities of understanding other people, their motivations, whether they lie and so on. This made our prefrontal lobes get much bigger to accommodate the recursive nature of interactions between a group of people (what if he thinks I did this and then she thinks that’s bad, and then what do they as a group think about that, etc.)

Information is the ultimate form of non-rival good, and we are evolutionary predisposed to share it because it accrues value to us, without taking anything from us. We evolved to share and to share in experiences, which is what media metaphorically replicates; because we experience media as real, or don’t really register the difference at an emotional level. In a broadcast world, even while watching on our own, we still knew that lots of people were watching the same thing at the same time.

Every year Mariah Carey makes about $1m from her Christmas song (if you want to make money as a songwriter, pick a (probably lesser known) holiday and write an anthem for it). We want to have seen and heard things other people have seen and heard, and that was the model upon which media economics rested, and then gained alpha through the network effects. But what is famous when there are no tops and no pops? What does media become when it’s only for one?

Featured image by Matthew Henry