Recently my wife Rosie and I went on a cycling holiday in the south of France and we had a delightful time. Not being on my phone and doing hours of mostly mild exercise instead in beautiful surroundings did wonders. The tour operator creates the itinerary, makes bookings at various B&Bs en route, and takes your luggage from one to the next. They provide a playbook of directions and mile markers and a bike computer tallies your progress to keep you on track. At least until you make your first error and the odometer is no longer in sync with the perfect ride in the guide. Each day we had only to get from point A to point B. Rosie suggested we look for different coloured items each day to photograph as we cycled. A side quest, I said, and so we did.

The trip had come about because we attended a wedding in the area a few weeks before and had occasion to cycle from some place to another and remarked on how fun it was to ride a bike again. We used to cycle to work in New York and it was one of the most reliably fun parts of the working day, often when I felt most free. We had a break between projects intending to spend some more time in France and I remembered my brother mentioning he had done walking holidays in Europe. We wondered if such things existed for cycling. They did. A detour becomes the path.

Perhaps my most vivid memories of the endless expanse of Skyrim, a mythical open world in the role playing game ‘The Elder Scrolls’, come from a side quest

I spent too many increasingly frustrated hours trapped inside a village I had come valiantly to aid. I couldn’t understand why the villagers kept attacking me whenever I left the building I woke up in. Playing primarily last thing at night certainly didn’t help my mental acuity, but the moment I realized I had become a vampire I was elated and absolutely furious and I will never forget it. The game is so large and woven with side quests the joke is — Skyrim had a story?

In order to experience the side quest, one must know the story. We are a forward-looking species that makes sense of the world and ourselves through stories. Stories about who we are and how things are and should be. Promises, predictions, and plans are all stories about the future. Humans have a unique penchant for prospection, the act of looking forward in time, and we use it to make choices in the present. We are invariably wrong about the specifics, but we can apply broad principles probabilistically. The context of our birth is beyond our control and hugely determinant, but we are also agents. If we exercise, we are likely to be healthier. More education correlates with higher lifetime earnings. Beyond that we are mostly terrible at specific predictions, as the stock market demonstrates. We know the average shape of a life but nothing about the details of ours.

People and corporations used to make grand five-year plans

We always understood that we are subject to the vagaries of chance but we have to consider the future because the return on investments can take years. If I commission a factory that takes x years to build, will the market support that increased level of production in x+ years time? What if fashion or the situation has changed? If I go to graduate school for a specific technical job, will it have been replaced by AI by the time I graduate, saddled with student debt? Despite the fact that our predictions will be wrong, we have to act as though we know the story. We had to pick three subjects to specialize in at age sixteen at school and they had to be suitably connected to appease university administrators (or the algorithm, today), merely garnished with extra-curricular side quests.

In David Epstein’s book Range, he explores research that suggests people tend to be happier in their jobs if they sample a few different things earlier in their careers when the switching costs are much lower. They are more likely to find something that suits them because they didn’t really know their story.

Companies have mostly reduced their horizons to annual planning cycles. Those plans are based on assumptions, ones that changed dramatically in March 2020. Companies then began to realize the consequences of the genuinely strategic decisions they had made. The economic efficiency of just-in-time supply chains is a strategic choice that assumes no interruptions. Efficiency is a limiting factor on resilience. A commercial aircraft flies with two pilots and two jet engines though it needs only one of each to fly. The redundancies make the system resilient. Preparing oneself, or a company, as best you can with what is known for an unknown future is strategy.

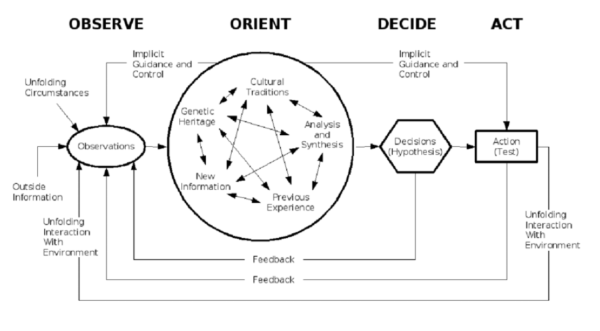

Modern strategic thinkers have developed responses to the protean world in formulations of agile or adaptive strategy. One of the most famous examples is OODA: Observe Orient Decide Act. It was developed by a military strategist and fighter pilot called John Boyd for making decisions in aerial dogfights. It broadly resembles all strategic processes but has a particular focus on speed and embracing the true nature of a situation.

In the notes from a talk “Organic Design for Command and Control“, Boyd wrote:

“The second O, orientation—as the repository of our genetic heritage, cultural tradition, and previous experiences—is the most important part of the O-O-D-A loop since it shapes the way we observe, the way we decide, the way we act.”

We can’t control what happens, but we can impact how we are oriented to react to our observations

If we see them clearly and invest and invent accordingly we can create innovations, side-lines to the existing business, and unlock new markets. At the same time, we need to ensure that the system doesn’t sink or swim on speculative bets.

In January 2013, I proposed to Rosie (she accepted) and suggested we leave New York and travel on something of a sabbatical. That side quest turned into the story of our life, living nomadically, for the next decade. Life is all side quests until the story unfolds, each random interaction leading to a new fork in the road. There is a great sense of freedom to indulging in a side quest, flipping the bird to the culture of productivity and its steady dollar drumbeat.

Why not sample a few different stories, see what suits? How can you invest in your own resilience? What’s the origin story of your next decade? And if you are persistently frustrated, at least consider the possibility that you are stuck in a side quest.

Featured image: Ussama Azam / Unsplash